by Virga Popovaitė PhD student in sociology at Nord University

While inquiring how maps are used by Norwegian rescue services, I have observed various operating rooms where responders use maps. This blog post is adapted from my notes onboard a rescue boat in Northern Norway. With it, I want to emphasise the extent of settings and more-than-human interactions that following maps can lead to. It illustrates how such interactions materialise something that might not be instantly visible.

… The engine was on, the lights were switched off, and the boat was unleashed: We were ready. Apart from the lights from the port, it was not so bright on the rescue cutter’s bridge. The main light source was a dim red lightbulb above the captain’s seat, with everything else set on the night mode, not to interfere with sensibility to light. While slowly passing other vessels in the port, the captain explained the intricacies of navigating at night, which is based on light and colour coding – an old system of lighthouse, buoys, and other navigational aids.

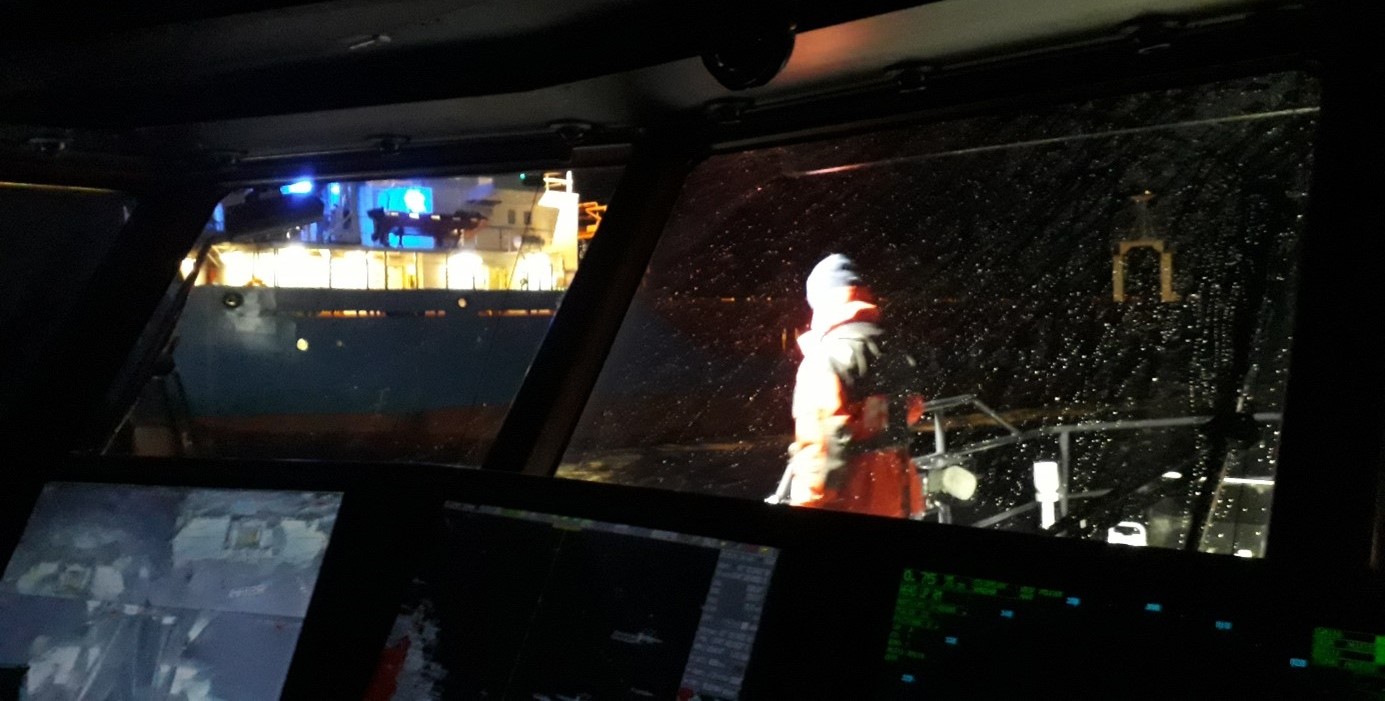

The layout of the vessel’s bridge outlined the roles of the team members. The main navigator sat in the middle, having a good oversight of the windows and four computer displays slightly turned towards them. The displays were modified so the person sitting on the right could edit necessary information. The machine officer responsible for the engine had their own set of screens, visibly turned straight to their chair, thus parting the space from others.

With the port behind us, the view outside was slowly changing. On the right side, the last lights of the town were replaced by faint silhouettes of snowy mountain tops, glooming in the dark. As we entered a patch of open sea, the waves got rougher and bigger, even though the wind was pretty mild in comparison to a storm which had just passed. The boat was rocking to all sides. With every stronger toss, I would lose sight of the map. While the darkness outside hid the waves from one’s vision, I felt their presence through my tightened muscles. Their appearance materialised on the radar, with larger waves leaving their footsteps on the display as lightened spots.

The mission itself was the same as the one I observed before. We were to meet a certain vessel out in the sea and pick up its pilot. It meant approaching a moving ship and maintaining a distance so small, that the person could climb down ladders onto our rescue boat. With both vessels still in motion and the presence of rougher waves and wind, this seemed far from a simple feat. While the captain focused on staying as close as possible, a team member helped the pilot outside. All went according to a plan, the person got onboard, the teammate clipped back the side rope, and they both came inside to the bridge, followed up by what seemed to be a casual chat. The captain later commented that, while the level of coordination requires observation, practice, and skill, it would be very different if approaching a stranded ship. In that case, wind would play an important role. As the wind is invisible in the sea charts or the radar, one should observe the waves, the ship’s tilt, and anything that could help deciding the direction of approach. …

Virga Popovaitė is a sociology PhD student at Nord University, Bodø. Her research critically investigates the response capacity of Norwegian rescue services in the Arctic through their use of maps. The project interrogates mapping practices, focusing on materiality, localities, infrastructure, and knowledge production. It cuts across sociology, critical cartography, emergency preparedness studies, and science and technology studies. Having a clear footing in a posthumanist tradition, Virga positions herself as a more-than-human sociologist.