A fieldtrip story from Kalaallit Nunaat

By Birgitte Rigtrup-Lindemann, Doctoral Candidate at Nord University, together with Helena Gonzales Lindberg, senior researcher at Nordland Research Institute

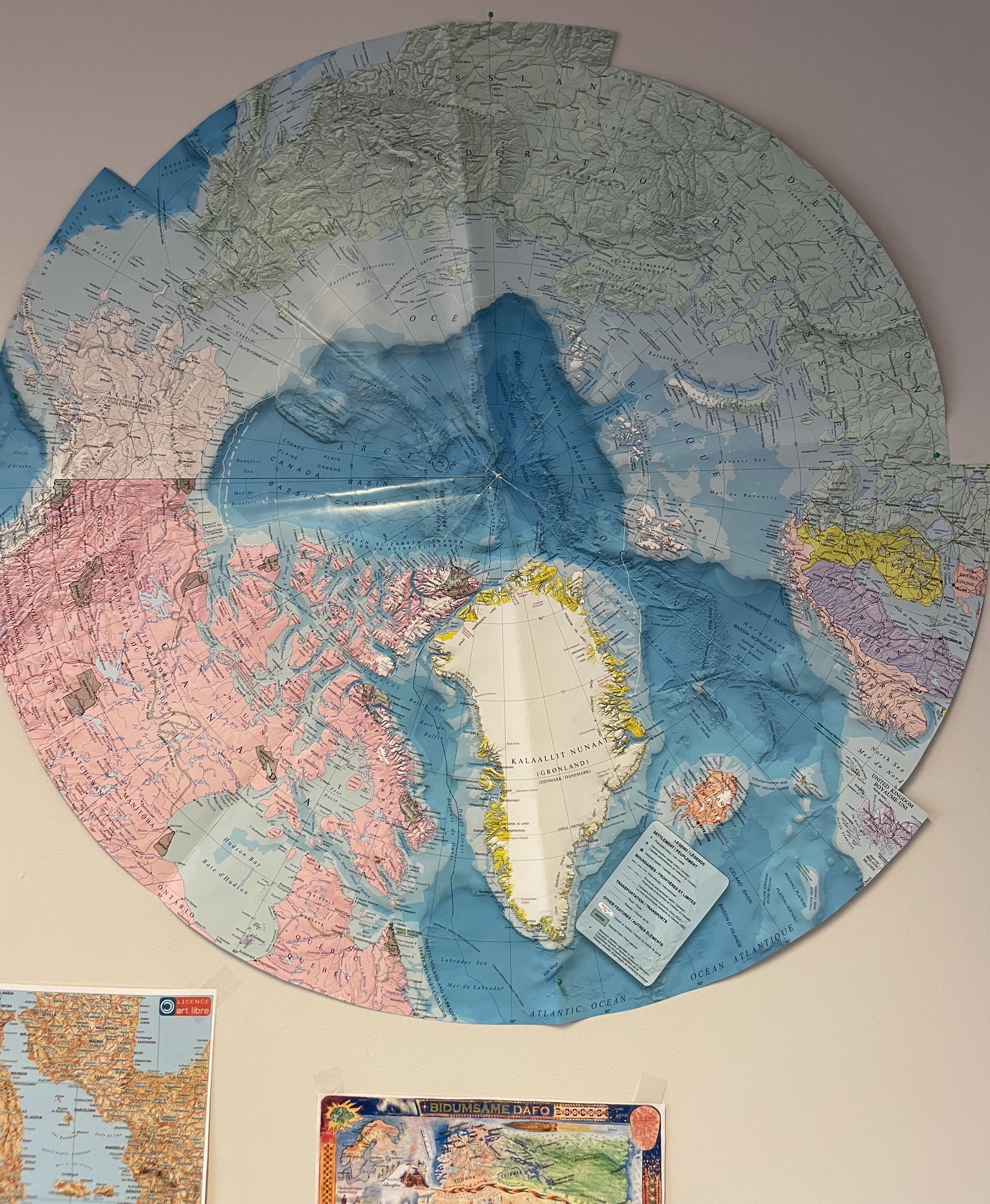

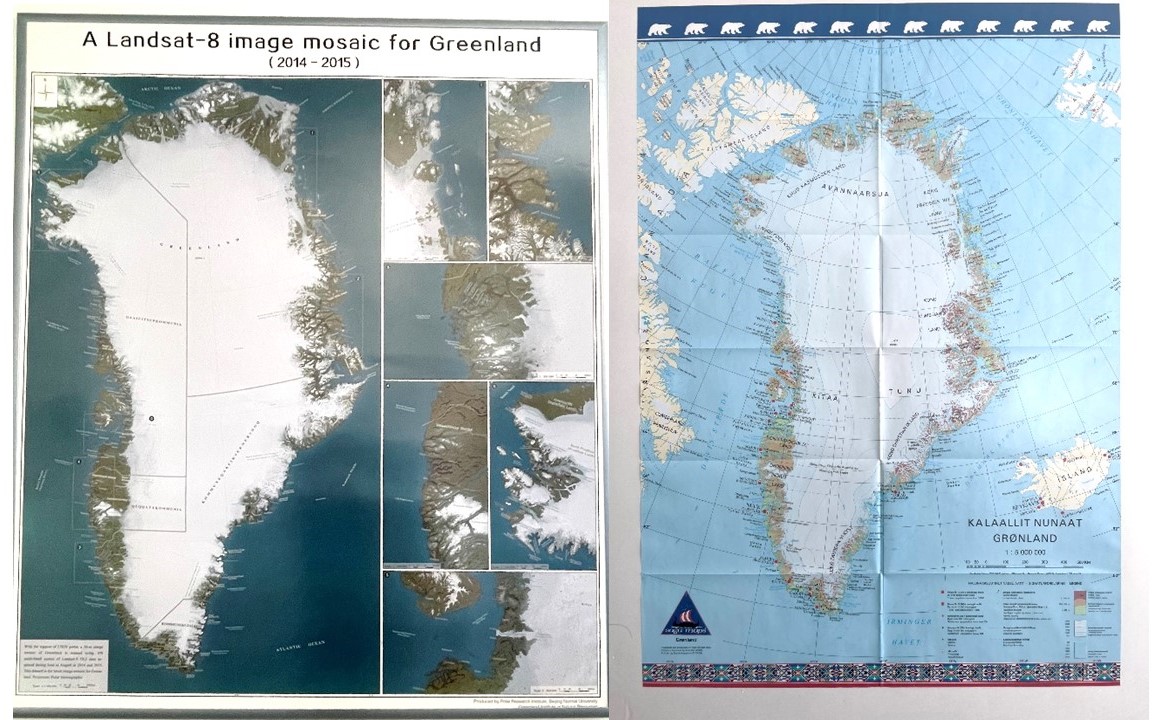

Looking at the maps covering the walls of my colleague’s office I notice a round map showing the Arctics and my eyes are caught by the huge country Kalaallit Nunaat centred in the middle of it, all showing off her massive amount of ice.

It is only few days before I am off to start my first of several fieldstrips to the exact same great land of Kalaallit Nunaat. By coincidence and because of a common interest in maps I am invited in by the dedicated map enthusiast and co-researcher Helena Gonzales Lindberg to have a chat about maps, the arctic and Kalaallit Nunaat.

Unlike Helena, who grew up in Norway, I am from Denmark and had my primary education in a public school in Denmark in the 1990’s. Looking at the eye-catching representation of Kalaallit Nunaat in the middle of the map, from the viewpoint in an office in Sápmi, I remember how I was presented with a very different map when growing up, where Kalaallit Nunaat was presented together with Denmark.

I specifically remember how the big school maps commonly showed Kalaallit Nunaat located in a tiny bottom corner of the map, massively reduced in size to fit the frame. Of course, we’ve been taught how maps have a difficulty in representing actual sizes of continents and islands on a 2D surface. Although, I theoretically knew that Kalaallit Nunaat was much larger than shown on the school maps, I always imagined the big, iced country as being a little smaller than southern Sweden.

Talking to Helena about my memories we came to discuss how the representation of Kalaallit Nunaat would be in its own country, having in mind their colonial history with Denmark. What maps would I find in public spaces in Nuuk and Maniitsoq? How would Kalaallit Nunaat be represented in maps at public schools, at museums, in tourist shops or at the university?

And how would Kalaallit Nunaat be placed in maps as a part of the Arctic?

I sat out on a mission to look for maps of the great country in its own land.

…………………………………

One month after – safely returned from a month at the western coast of Kalaallit Nunaat, I look at the maps I found during my stay.

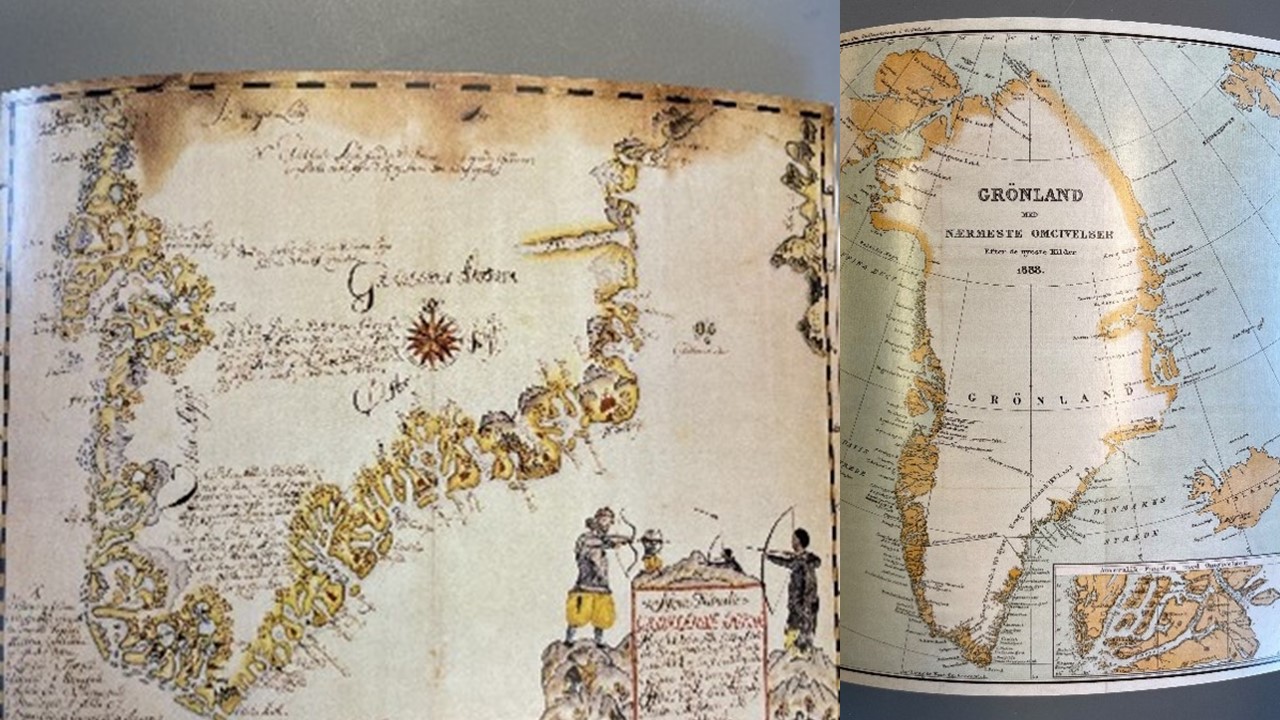

With me I have posters and postcards showing maps from 1737 drawn by Danish/Norwegian colonisers, historical maps from 1888 and new maps from 2018. Also, I have pictures of maps I found on my way; maps produced by Saga maps or by Polar research institute in Beijing. And I wonder: What can we read from these maps?

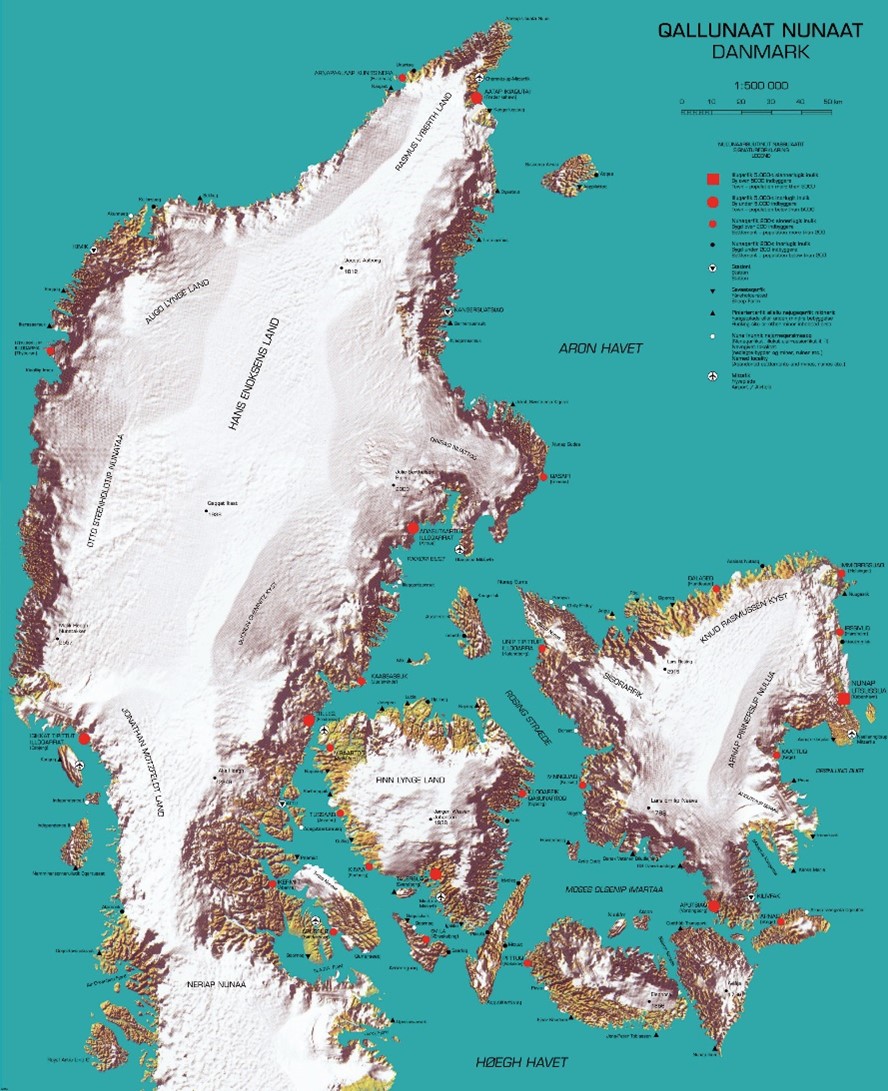

Of all the maps I found, I found no maps using only Kalaallisut (Greenlandic) as the language to name all the places on the maps. All maps are either in Danish, Danish/Kalaallisut or English/Danish/Kalaallisut. Remarkably interesting are the place names used on the maps where names of the places are referring to names or places from outside of Kalaallit Nunaat. Often it is names referring to Denmark: “Kong Christian d. IX’s land”, “Kronprins Frederiks Land” or “Knud Rasmussens land” but also names like: “Liverpools kyst” or “Washingtons Land”.

Looking at the maps, they tell me a story of powerrelations and they tell me a story about power relations in a context of time and history. They tell me a story about colonialism.

Back in the office in Bodø, my colleague and always dedicated map enthusiast Helena shows me another map she found while I was away. In this map, the artists Inuk Silis Høegh and Asmund Havsteen-Mikkelsen show Denmark as being colonised by Greenlandic-Inuit as well as the Arctic climate. This map twists the story and places names of important figures in Greenlandic history onto ice-covered Danish islands and peninsulas. I find this map a great example of how art can give us new critical insights, awaken curiosity, and inspire other ways of thinking about Kalaallit Nunaat and the Arctic.

Maps are not objective representations of the world. They contribute to shape our understanding of the places that are on the map, both in the way they are shown, such as the chosen map projection, use of colours, signs, and place names, but, importantly, also in what they do not show.

My mission to look for maps in public spaces during my fieldwork in Kalaallit Nunaat gave me an important insight in the way Kalaallit Nunaat is represented to the world and how it is and has been placed in a historical power relation. This insight calls for reflections that I can take with me into my continuously PhD-journey.

Birgitte Rigtrup-Lindemann is a PhD Fellow at Nord University’s Research division for Sociology, Research Methods and Philosophy of Science. She is currently conducting fieldwork as a part of the project INDHOME (Indigenous Homemaking as Survivance) where she is looking at homemaking practices as cultural survivance among Inuit-Greenlanders living in and outside of Kalaallit Nunaat. Birgitte is inspired by feminist methodology together with queer, post-colonial and indigenous theories.

Helena Gonzales Lindberg is a senior researcher at Nordland Research Institute in Bodø, Norway, working on a wide range of research topics related to the Arctic region. She wrote her PhD thesis about the constitutive power of maps in the Arctic (Lund University 2019). Helena is constantly curious about the ways that maps affect our thinking about places in the world, “others” as well as ourselves.