What is North Sami and Norwegian doing in my English class?

Classrooms around the world are becoming more culturally and linguistically diverse, but are the attitudes, practices and approaches reflecting this diversity? Unfortunately not. Even though multilingualism, as a phenomenon we read about or experience in our daily lives, is perceived as a positive attribute for societies and individuals, in educational settings it is still misunderstood, and mostly excluded. This reaction to other languages in the classroom results in exclusionary language and alienation of the students. But, why are we so afraid of different grammars and sounds and words and ideas in our classrooms? Perhaps, because we are understandably apprehensive about allocating precious classroom time to something that is rarely perceived as a resource by most monolingually oriented curricula.

Being someone who lives and works with languages, I wholeheartedly embraced the opportunity to integrate a ‘Sami focus’ into my English class. Now, I don’t speak any of the nine Sami languages, and neither do my students. Yet, in Norway, the curriculum explicitly states that students must learn about Sami culture, history, social life and rights:

Gjennom opplæringen skal elevene få innsikt i det samiske urfolkets historie, kultur, samfunnsliv og rettigheter. Elevene skal lære om mangfold og variasjon innenfor samisk kultur og samfunnsliv. (Overordnet del, s. 6)

The Sami National Day is celebrated on an annual basis on 6 February. Sami Week at Nord University includes multiple events, for example, lectures on Sami history, exhibition of pre-school children’s arts and crafts and yoiking performances from the music students. Very enjoyable, but completely absent from the my classroom reality.

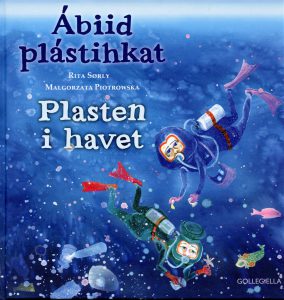

Well, quite a lot, actually. Instead of dealing with indigenous cultures from a surface-level, folkloric perspective, for example, by looking at what the Sami peoples eat and wear, where they live and what they do (i.e. reindeer herding), this picturebook allows for a more nuanced and contemporary approach. It gave us the tools to explore, in more depth and in English, how indigenous peoples are tackling serious environmental issues and struggling to protect their ancestral homes. Even though the text in North Sami and Norwegian indicates a Norwegian setting, the reader is introduced to two Maori female scientists, from Otago in New Zealand, investigating the effects of plastic and sea pollution on marine life. This twist is pictorially striking on the first page: the interplay of visually strong images, that is, traditional face tattoo and white lab coats, supported by the straight-forward factual language of introducing characters and setting, is juxtaposed by the two languages, thus decentering the readers’ expectations.

This picturebook, with a beautiful palette of blues and pinks, depicting the different moods of the sea and evocative of the arctic skies in winter, respectively, ends with a call for environmental action:

Kan vi alle finne fem ting vi kan gjøre for å slutte med plast?

Sáhhti og mii buohkat hutkat vihtta vuogi, mainna heaittašeimmet plástihkaid geaveheamis?

Can we think of five things we can do to stop using plastic?

In answer to the above question, the post-reading activities the student teachers envisaged included an investigation of indigenous peoples’ struggles highlighted their special relationship with the land, which is one of respect and co-existence as opposed to dominance and exploitation. Based on the website, *Teaching Indigenous Knowledge, the student teachers explored other indigenous peoples’ struggles to protect their land; they worked on presentations and shared what they learned with their classmates to inspire important discussions around the pedagogical implications of this work. Further potential school projects included making a poster out of plastic from home; inviting a Sami guest speaker to the classroom; counting the number of plastic items in the home, in a cross-curricular project, which would include the Social Sciences, Math and Sustainability

What about the language(s)? We had some serious meta- and plurilinguistic fun, using intercomprehension, experimenting with translanguaging approaches, developing metalinguistic skills, practicing noticing strategies, looking for transparent words / cognates, working out the morphosyntactic structure of North Sami by comparing sentences to Norwegian and English, and hearing North Sami sounds with the help of technology. In order to ‘hear’ North Sami, we used the following website, *Your Voice Matters: for example, listen to the blurb on the back of the book reproduced below, by typing it into the space provided on the website, and be transported to another phonological world:

Dutkkit Aihe ja Whina johtiba mearaid mielde Otagos, New Zealanddas gitta Norgii. Soai áiguba dutkat muohtofávrofállá mii lea rievdan fiervái. Fállá ruoktun leat trohpalaš ábit. Manin son fális rievddai nie guhkás, gitta Gáŋgaviikka fiervái?

We would also like to leave you with a linguistic call to action:

Can you guess these North Sami words in the picturebook?

Plástihkat Kompássa teknologias plánehta Norgga kollegain konferánsasále

… and conclude with a pedagogical call to action:

Bring linguistic diversity into the English classroom, not only to support and validate the children’s own languages and identities, but to join the ongoing multilingual turn in language education predicated on viewing multilingualism as a resource, with language knowledge serving as a basis for learning further languages and as a link to openness to others.

*We would like to acknowledge the support of Sandra Maria Nystø Rahka, Universitetslektor and Research Fellow at Nord University, Helen Margret Murray, Assistant Professor of English at NTNU and creator of Teaching Indigenous Knowledge, and last but not least, the student teachers.