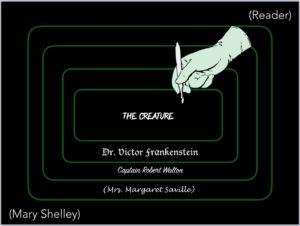

At my recent lecture on Frankenstein, I mentioned the novel’s famously contorted narrative structure:

I’m particularly interested in the way that Mrs. Margaret Saville functions as the unseen, unheard, but ultimate arbiter of narrative, for it is only through her release of Captain Walton’s letters that the story is known to us. As part of the forthcoming special edition of Litteraria Pragensia, which I’m co-editing along with my colleague at the University of Tromsø, Professor Cassandra Falke, I have written an article that addresses my reading of Margaret in more detail and with a narratologist’s eye, a snippet of which is reproduced below:

(from: Hanssen, Jessica Allen. “Unnatural” Narratology, Frame Narrative, and Intertextuality in Frankenstein. Litteraria Pragensia, Volume 28, number 56. (December 2018).

At the outset, there is a readerly quality to the text due to its presentation as letters from Captain Walton to his sister Margaret Saville. It’s a savvy choice, because it allows for a third person, omnipresent point of view, but also with all of the advantages of the first-person confessional. Time here is linear and conflated, to account for the actions of just one person. Several weeks and even months go between Walton’s letters to Margaret, where his movements and encounters are faithfully recorded. And yet, I am called in the interstices to ask, what was Margaret doing during those weeks? Does Walton even care? Walton makes sure to describe his own exploits to her, in explicit and rich detail, but any mention of her own are missing: does she exist as anything other than a convenient recipient? Margaret’s story is an unwritten one, but it still exists, outside of the margins of Frankenstein, as an essential element of the framing device. Margaret is more of an abstraction than a character, the perfectly silent, but devoted, woman, but her presence guides the narrative as we understand it; it is all filtered through her as its intended recipient. Without the ability to re-create Margaret’s movements during the interstitial spaces between letters, the reader is thus left wondering: is her life equally or even at all adventuresome? Does she have a friend as dear as Victor to Walton, to tell her story to and make her “blood congea(l) with horror,” (Shelley 151) as Walton boldly assumes that his words do on her behalf?

Clearly, Margaret is the kind of educated, compassionate, and sophisticated woman to whom the story of Frankenstein would have been compelling, which in itself is interesting, but this can only be inferred indirectly, through Walton’s choice of her as recipient and last of the line of narratees. We learn, only after the entirety of Frankenstein has passed, and thus her service to Walton is completed, that she has a “husband, and lovely children,” (Shelley 151) but neither of these are likely suitable further recipients of the tale. This is, perhaps, intentional on Walton’s part: Walton intended to whisper his horrible tale – and the horrible promise he has made to succeed in achieving the creature’s demise – into her Pactolus ears, thus unloading his burden. The simple fact that we the reader engage Frankenstein only as mediated through Margaret’s permission, becomes, then a subversive act of narrative. Just as the creature’s female companion still exists, albeit in parts at the bottom of the sea, Margaret’s lack of characterization becomes more powerful than her physical presence could have been, a negative characterization in the sense of negative space in the visual arts. We are forced to create her might-have-been for ourselves, a truly writerly experience where highly significant parts of the linear narrative are not explicitly narrated but are nevertheless a part of the novel’s matrix of meaning. In that sense, we do what Victor could not bring himself to do: we create a woman.

Work Cited:

Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft. Frankenstein. Edited J. Paul Hunter. Norton, 2012. p. 151.