Indigenous Homemaking as Survivance: Homemaking as Cultural Resilience to the Effects of Colonisation and Assimilation. (INDHOME)

- Excellence

1.1 State of the art, knowledge needs and project objectives

- a) State of the art and knowledge needs

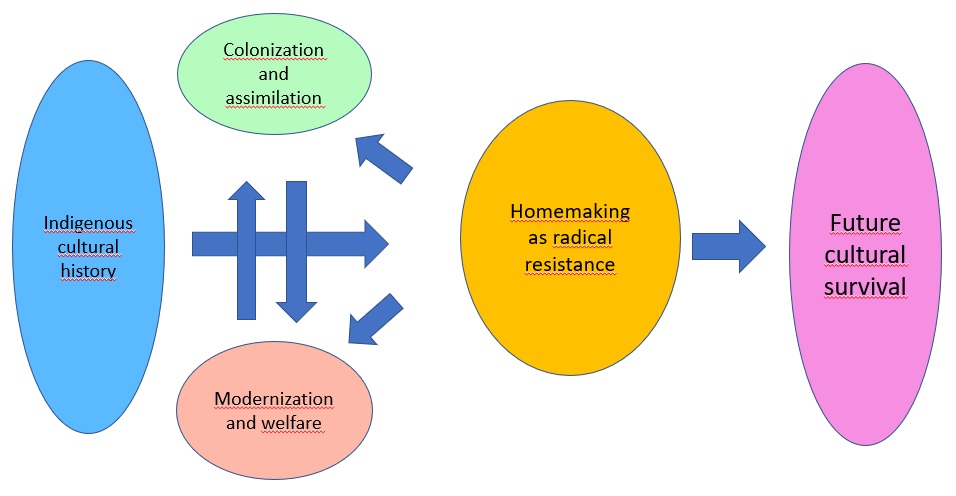

INDHOME will address the knowledge gap concerning how Sámi and Inuit homemaking as an everyday life practice is a form of cultural resilience and survicance after the effects of assimilation, colonisation and post-war welfare policies such as housing policies in the Scandinavian countries. Homemaking – creating a space that provides shelter, comfort and a strong sense of being oneself – is one of the most foundational cultural practices, yet curiously overlooked. While housing is a practical, material and economic foundation to the experience of home, a home is a relationship that is created over time, connected to a sense of belonging(1). Homemaking can be seen as a form ‘survivance’, which involves more than just survival. It is a way of nourishing Indigenous ways of knowing, including the complexity, contradictions and self-determination of Indigenous lives(2). Homes are spaces that traverse time, place and social status, as dynamic social constructions that are variously related to policies, places, families, kin, self, gender, feelings, journeys and practices. It is a place for togetherness, care and wellbeing, coming together and creating a ‘household’(3,4) Homemaking is therefore crucial for social reproduction, social identities and social transformation, where the “trivial” everyday practices of homemaking in everyday life are interconnected with ontologies and politics(5) This includes the spiritual dimension, where the home includes more than the living, linked to, for example, “unrest in houses” and traditional rituals(6).Houses and homes exist both as physical entities, esthetical objects, social institutions, sites for labour, emotionally rooted places in relation to memories in the past, and a link between the past and present, deeply rooted in both families, kin, local communities, landscapes and nature (3,7).

The Scandinavian countries share some basic features regarding history, culture, welfare and politics. It counts to all three countries that less research has been concerned with the indirect assimilation induced through often well-meaning welfare policies such as housing and the links between the housing policies in the past and its consequences for Sámi and Inuit homemaking. The same can be said about the debates on colonisation, which up until recently have mostly been concerned with cultures and societies in former colonies in non-European territories (8). The Scandinavian countries have often been presented as outsiders performing “innocent” colonialism(9,10), with equality-oriented welfare systems, strong democracies, economic competitiveness, concern with aid, peace building, and cooperation. This image has silenced the internal colonisation and assimilation of the Indigenous Sámi and Inuit and other national minorities. Colonisation has often been understood in relation to specific events and control over land and water. We argue that colonisation can also be studied as a structure, not only an event (11), where the invasion is connected to elimination of the colonised, a dissolution of Indigenous societies, their structures, culture, values and even history through assimilation, replacing them it with the colonisers’ societal principles. While, for example, the Norwegianisation policy was an explicit attempt to replace Indigenous language and culture with Norwegian(12), this project is more interested in the indirect assimilation of welfare policies induced through often well-meaning welfare, that unintentionally involved a continuation of colonial structures, materialised in people’s everyday life.

The role of the church in the early colonisation and its effect on the Sámi society is well documented(13). Norway had a forced assimilation policy, the so-called Norwegianisation policy from the mid-1800s, that did not formally end until the 1980s(12). The schools’ role in the Norwegianisation policy has been well documented(12). Sweden’s policy towards the Sámi combined paternalism with segregation towards the reindeer herding Sámi (the so-called “Lapp shall be Lapp” policy), while other Sámi experienced assimilation (14). In the 1960s and 70s, we can see a change in research on the Sámi, from perspectives focusing on the Sámi as “primitive” people, to colonialism and poverty(15) and the Sámi minority situation perspectives(16) that later has been criticized for victimization and not including Indigenous agency and empowerment. In the 1990s, identity and ethnic mobilization became important issues in research, and above all, the inclusion of researchers with Sámi background (17). For Greenland, the period 1953-1979 (Greenland became integrated into Denmark as a county in 1953 and obtained Home Rule in 1979) arguably saw the most drastic and swift changes to Inuit lives(18) It is also a period in living memory of the elder generations of Greenland. Although often hinted at in political debates, the links between postwar welfare policies and contemporary Greenland have only rarely been the object of systematic research. Isolated harmful effects of the assimilation or Danification policies taking place in this period have been topics of limited research. This counts for the unequal wage system (the “Birth-place criteria”)(19) , the case of the “Legal Fatherless” (20), the “Experiment Children”(21), the policy of closing smaller settlements and moving people to larger towns (the “concentration politics”) (22,23). However, larger systematic studies of the postwar grand welfare schemes and their harmful effects to the Greenlandic population are needed.

We argue that homemaking can be seen in relation to decolonisation, that can be defined as (re)negotiation of power, place, identity and sovereignty(24,25). It is not a reaction to colonial power in a binary way but a rather messy, dynamic and contradictory process (24) While there is extensive research on the colonisation, marginalisation and discrimination of Indigenous people (16,26) and its relevance for expressions of identities (10,16,17,27), there is a need for comparative, Scandinavian research on Indigenous cultural resilience(28) decolonization(24,25) and survivance(2). We as researchers need to move beyond reproducing stereotypical images of Indigenous people as damaged and use research perspectives that envision the resilience, hopes, visions and creativity of lived Indigenous lives(29). This is beneficial for society at large, since a peaceful and stable society is something that is achieved through a wide-range of respectful collaboration and cooperation, something that is highly relevant in today’s increasingly polarised world.

- b) Project objectives

- Document and analyse the historic housing policies in post-war Scandinavia and present a brand new study of networks of policy makers, architects and housing developers within Scandinavia for the period 1945-1979.

- Contribute with a ground-breaking, transnational and interdisciplinary study of Indigenous homemaking past and present in the Scandinavian countries and Greenland concerning how it has been affected by Scandinavian post-war welfare-state policies and how contemporary Indigenous practices of everyday life can resist further elimination of Indigenous cultures.

- Develop new knowledge about homemaking practices and its relevance for Indigenous cultural resilience and survivance and assist public and private sectors, stakeholders, NGOs and Indigenous communities in developing new policies and practices.

- Contribute to new, desire-based and optimistic conversations about Indigenous lives that can give hope and visions for the cultural resilience and survivance of Indigenous people.

1.2 Research questions and hypotheses, theoretical approach and methodology

- a) Research questions

Can Sámi and Inuit homemaking as an everyday life practice be seen as a form of cultural resilience after the effects of assimilation, colonisation and post-war welfare policies such as housing policies in the Scandinavian countries?

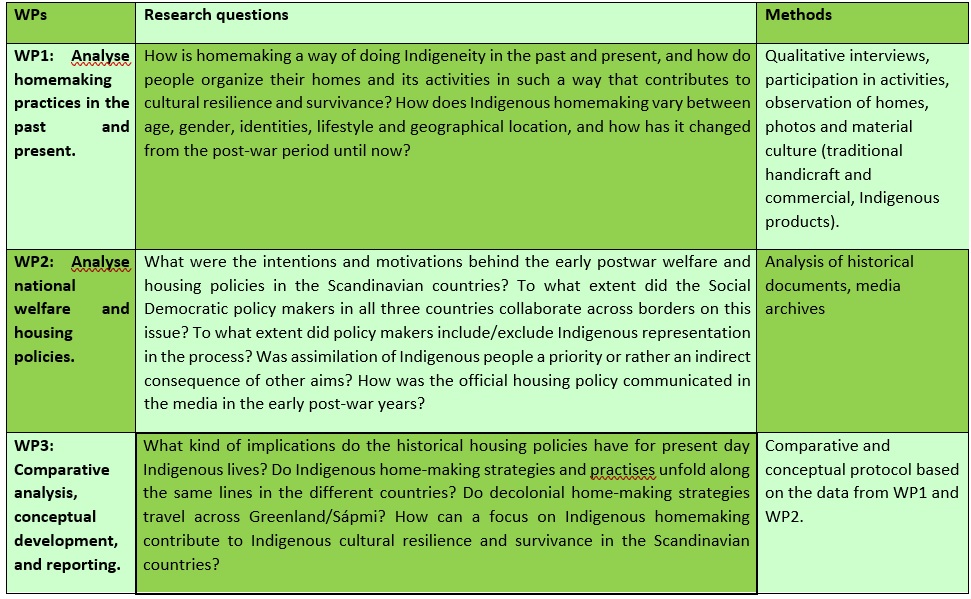

This research question is operationalised through work packages with their own sub-questions (except WP4. A more detailed description of the work packages can be found in 3.2.

b) Theoretical approach

INDHOME is inspired by postcolonial (8,10), decolonial and Indigenous perspectives (25,30), which also has implications for the research design. As we state in 1.1, we want to study colonisation as a structure, not as an event(11) Decolonisation, on the other hand, can happen through formal political processes, but also through everyday life practices, such as Indigenous homemaking. Through our focus on homemaking as cultural resilience(28) and survivance(2), we use perspectives that transcends the dichotomies that reflect false ideas about authenticity and traditional lifestyle, denying that change exists in all societies, including Indigenous societies (30). Rather than studying homemaking as passive repetition of static notions of traditional culture, knowledge and values, we see homemaking as an active process in people’s everyday life that involves negotiation of structures and agency, the past, present and future. While the notion of resilience in psychology usually describes an individual’s ability to do well despite adversity rather than its systemic roots, cultural resilience focuses on the collective level, where cultural resilience draws on traditional knowledge, values and practices, in addition to ongoing responses to new challenges in relation to the dominant society and global networks(28).

We will study Indigenous homemaking practices in everyday life as a way of maintaining Indigeneity, and a form of cultural resilience(28) and survivance. Inspired by theory of practice (31), we will focus on the practical negotiation between structures and agency through concrete human actions. Bourdieu (31) shows how the home corresponds with social distinctions, such as light/dark, public/private and male/female, reflecting both public conduct and religious beliefs through various domestic routines, layout and furnishing. This shows how organisation of the home not only reflects the societal structures and worldviews, it plays a crucial role in maintaining, reproducing, modifying and resisting them. Structures can be power relations, underlying schemes, codes and values, while practice is a concept that describes the life as it is lived, where social actors negotiate social norms and structures(31). Practices are also connected to ontologies and the active mode of shaping political realities, such as decolonization. Politics is shaped and reshaped through the reality that we live in, where the ‘real’ is implicated in ‘the political’, and vice versa. The political is not solely connected to larger societal structures; it is also performed through practices of everyday life (5).

- c) Methodology

We are inspired by decolonising methodologies (25), that sees research as an institution of knowledge embedded in a global system of imperialism and power. While research has often been conducted by outsiders, with a lack of acknowledgement of Indigenous peoples interests and needs, this project includes Indigenous researchers, as well as Indigenous individuals, centres and organisations represented in an expert group. It is also based on an analytical acknowledgement that we as researchers do not solely document the past or the present, but that we are storytellers that also choose what kind of stories that are told about people(26). Our methodology involves an interdisciplinary approach, with historical, archival studies, qualitative interviews, observation and photos of home interior and activities. We will explore the intricate relationship between colonisation and decolonisation, the past and the present, the larger societal structures and the small and “trivial” materiality and practices of everyday life, as well as local Indigenous homes and their national and international interconnectedness.

We will interview ca 30 individuals from Norway, 30 from Sweden and 30 from Greenland and Denmark. We seek to recruit PhD students with competence in Inuit and Sámi language and culture, and we have also included funding for research assistants who can conduct interviews in their native languages if needed. We will recruit interviewees through our own networks, the expert team, local Indigenous organisations and centres, social media, invitation letters through mail, and through snowball method. We aim to recruit people that will reflect the complexity and heterogeneity of Indigenous lives in communities in Sápmi and Greenland regarding identities, livelihoods, geographical localisation, age, gender, language and culture, and the different experiences regarding colonisation and assimilation. We have chosen not to focus on communities or cases but interview individuals from different communities in North, Lule, Pite, Ume, and South Sápmi in Sweden and Norway, and Kitaa (West Greenland), Tunu (East Greenland) and Avannaa (North Greenland). We will interview individuals in a minority or majority situation locally, and individuals living outside the traditional Indigenous areas, such as Oslo, Stockholm and Copenhagen. In this way, we can explore the complexity of Indigenous lives in Scandinavia today. In addition to studying Sámi and Inuit in Norway, Sweden, Greenland and Denmark, we have included Sámi researchers from Finland, Russia and the USA to provide input at all stages of the project, including an invitation to contribute to a published volume on Indigenous homemaking.

In the qualitative interviews we will use a semi-structured interview guide. In order to study the historic development as lived realities, part of the interviews will focus on elder members of the societies. We will explore historic examples of homemaking as culture preserving resistance to colonisation and assimilation in the past, and in this way analyse if and in what way there is a continuity between the past and present. We will explore the role of memories and feelings, the transition from traditional housing to modern housing, historic relocations, and the symbolic dimension of homemaking practices, including rituals. We will observe and ask questions about homemaking today through both activities and material culture such as art, photos, furniture, tools and decoration. We will invite people to share photos and make short videos from their own homes and include these in the interviews. We will also explore homemaking in relation to food production, cleaning, child care and work outside the home, practices that also reflect continuity and change in gender relations. Homes also play a crucial role in the socialisation of individuals into larger society. Some of the interviewees might have several houses that they define as homes, reflecting historic relocation due to welfare and housing policies, or connection to a nomadic or semi-nomadic lifestyle, such as reindeer herders and hunters.

INDHOME will also explore comparatively the historical Scandinavian post-war housing policies and how they have a common origin in a Scandinavian welfare state ideology that was shared across the Scandinavian region, albeit with certain national variations. The historical part is based on a comparative framework of entangled history, global history and connected histories (32,33). We will map, describe, compare and analyse how Western post-war ideals of modern housing and health served to undermine traditional indigenous lifestyle in the Scandinavian countries, and how this has contributed to changes in houses and Indigenous homemaking practices. We will focus on the development of the early post-war housing policies, based on a thesis that the historic housing policies studied were interconnected in multiple ways that simply reflect similar welfare-state ideologies. We will also explore possible network formations amongst both Scandinavian policy makers and Indigenous representatives in the period studied. We will do archival studies of historical policy documents, political debates and negotiations between Scandinavian and Indigenous representatives in the respective national archives in Sweden, Norway, Greenland and Denmark, in addition to comparative studies of architectural solutions employed in Sápmi and Greenland, respectively. Additionally, we will analyse and compare a sample of media texts, focusing on how the official housing policy was communicated in the public sphere in the respective countries in the early post-war years. We will use the following archives: Norway: Riksarkivet, Finnmarksarkivene, Arkiv i Nordland, Statsarkivet i Tromsø, Digitalt museum, Kystmuseene, Norsk Folkemuseum, Nasjonalbibliotekets database, Retriever. Sweden: Lappfogdearkivet vid Riksarkivet, Landsarkivet i Härnösand, Riksarkivet i Östersund, Instiutet för språk och folkminnearkivet och Forskningsarkivet vid UmU, Mediearkivet. Greenland/Denmark: Grønlands Nationalarkiv, Arkivet ved Nunatta Katersugaasivia Allagaateqarfialu – Grønlands Nationalmuseum, Arkiv (Nuuk), Arktisk Institut i København, Rigsarkivet, Danmarks Kunstbibliotek, Polarbiblioteket i København, Det Kgl. Bibliotek i København, Infomedia, archives of Atuagagdliutit, Sermitsiaq and KNR -Grønlands radio og TV.

INDHOME will be conducted in compliance with the requirements of Nord University’s internal ethical guidelines and those of the Norwegian Centre for Research Data and the EU GDPR regulation. Conducting research in Indigenous communities raises some extra ethical issues, and Scandinavian research history has numerous examples of oppressive research practices in Sápmi (34) and Greenland (35). It is therefore relevant to consider ethical considerations beyond individual consent (36), since this will be of great importance for the legitimacy of the research in Indigenous societies. There is no Sámi or Greenlandic institution that holds the power to give a collective consent on the behalf of the group as a whole (health research is an important exception here). We therefore seek to conduct the research in close partnership with Indigenous individuals, organisations, centres and communities.

One of the risks is recruiting especially elderly persons for interviews, due to health issues and lower digital competence. This is important since we want to describe the full heterogeneity of the Indigenous societies, and the elders are important voices in the project, since they can say something about cultural and societal change and their experiences related to them. The expert group and our existing networks in Indigenous communities, in addition to the open seminars in local, Indigenous communities, will be crucial in this recruiting process. Another risk is that we might fail to find historic documents that support our thesis or contain enough information. Here the comparative design, with access to different archives, might prevent this and provide a broader picture of the historic situation. Another risk concerns potential travel restrictions due to, for example, the current pandemic. A strength here is that we have research partners in all the different countries. Furthermore, we will conduct interviews through online platforms such as Zoom if travel is impossible. We have also included extra funding for data collection due to demanding travel costs in the regions where we will conduct our study. Undesirable effects on health, climate, environment or society during the project are low, and we will minimize the number and distances of flights or trips in other high-carbon vehicles, and use online workshops and meetings when possible.

1.3 Novelty and ambition

As we state in 1.1, INDHOME will fill the knowledge gaps between colonisation, assimilation, housing policies and Indigenous homemaking from a Scandinavian, comparative perspective. INDHOME presents several novelties: 1) The way that we will study how homemaking as ‘mundane’ and ‘trivial’ practices of everyday life are connected to larger political processes, such as colonisation, assimilation and decolonisation, is unique; 2) the comparative study of welfare state housing with consequences for Indigenous peoples has never been done before and will generate new knowledge about the relationship between the Scandinavian nations and their Indigenous people; 3) the historic study of post-war Scandinavian policy makers and architects in this context has not been done previously. Moreover, the ambition of the project is to fill the need for research on the interaction between ontologies and politics (5) in relation to how everyday life activities such as homemaking can be an active part of shaping our political realities as ongoing resistance to colonial structures. Rather than reproducing stereotypical images of Indigenous people as belonging to colonised and forever damaged cultures, we need to move beyond this victimising research perspective and focus on cultural resilience(28) and survivance(2) of Indigenous people. INDHOME will contribute to new empirical and theoretical perspectives on how ontologies, politics and everyday life interact and Indigenous cultural resilience and survivance. Through INDHOME’s interdisciplinary approach, we will develop new methodological perspectives on how to conduct research in Indigenous societies and how research can contribute to Indigenous resilience and survivance.

- Impact

2.1 The research project’s potential for academic impact

While there is extensive research on the colonisation, assimilation and identities of Indigenous peoples in the Scandinavian countries, there is a lack of systematic research on homemaking as a form of cultural resilience, survivance and decolonisation of everyday life, and how housing policies in the past served as indirect ways of assimilating Indigenous people in the Scandinavian countries. There is also a lack of systematic comparative research between the Sámi and Inuit people, which is striking given the shared history of Scandinavian colonialism, assimilation and the welfare state. INDHOME will therefore deliver ground-breaking research on both the colonial history and resistance of everyday life in the past and present of Indigenous people in the Scandinavian countries, which will be highly relevant for Sámi, Inuit and Scandinavian studies in particular, including the growing international field of Indigenous studies. Through the interaction with the expert group and a wider academic audience, the project will contribute to new knowledge about the effects of colonisation, welfare, politics and everyday life. An important part of the project is also to make space for new Indigenous networks within the Nordic countries, and we will also facilitate guest researcher visits at University of Greenland, one of our collaborative institutions, for the PhD students. Through the project’s design, we will also start new conversations about Indigenous methodologies and ethical responsibility. This might lead to new international publications and academic cooperation in the future within research fields such as Indigenous studies, minority studies, welfare studies, gender studies, and studies on truth and reconciliation.

2.2 The research project’s potential for societal impact (optional)

This project is important because of its focus on the cultural resilience and survivance of Indigenous people’s everyday life. Rather than reproducing an image of Indigenous people as forever damaged by colonisation, INDHOME seeks to explore the role of homemaking as an everyday life activity and its potential for being a form of cultural resilience and survicance. This is a way of empowering not only present day Indigenous people, but also Indigenous people in the past, because this is a way of painting a different picture than the reproduced images of helpless victims without agency. Through the project’s focus on desire-based perspectives in Indigenous research (37), the project seeks to move beyond victimisation and produce new knowledge about cultural resilience and survivance through homemaking as a practice of everyday life. Through developing an understanding of how homemaking is a crucial part of decolonisation, INDHOME will be of great relevance to the ongoing Truth and Reconciliation Commissions (TRCs) in Greenland and Sápmi. The ambiguity and strong reactions both in Greenland and Denmark towards the Greenlandic TRC shows the challenges of adapting a TRC model to the Scandinavian welfare states (37). Why reconcile? Because it allows Indigenous people to move beyond assimilation, integrate into the dominating society with the strength of their own identities, worldviews, values, practices and relations. This is also something that is highly beneficial for society at large, since a peaceful and stable society is something that is achieved through a wide-range of respectful collaboration and cooperation, something that is highly relevant in today’s increasingly polarised world. INDHOME is also relevant, given the fact that Bodø is the Cultural Capital of Europe in 2024, where Sámi presence in the region in the past and present is supposed to be an integrated part.

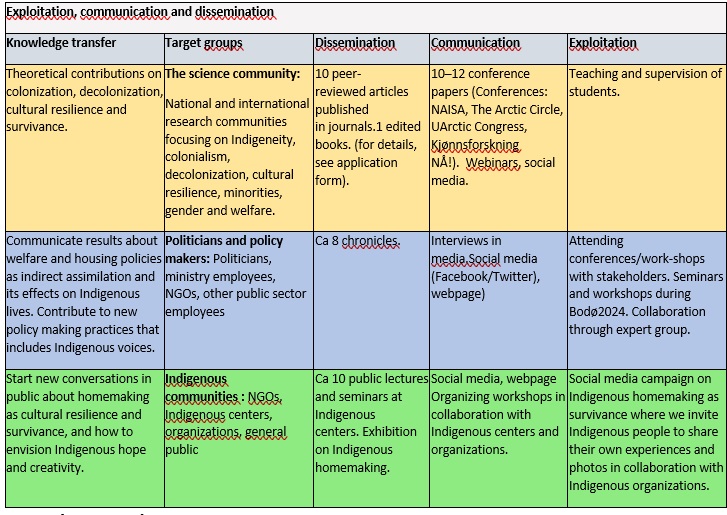

2.3 Measures for communication and exploitation

The administration of our objectives and tracking of dissemination and communicative efforts according to the project timeline is allocated to the WP5 leader (A.D). The project will contribute to conversations directed towards a wider audience regarding research and its relevance for Indigenous everyday lives, and through this potentially stimulate a greater enthusiasm for science within society, both among stakeholders and ordinary people.

- Implementation

3.1 Project manager and project group

The Faculty of Social Sciences at Nord University, Norway, will host INDHOME. The Project leader is Associate Professor Astri Dankertsen, Norwegian Sámi expert on Sámi identities, colonisation, Indigenous perspectives, gender perspectives, urban Indigeneity and activism. She is a member of the NAISA Council, the leading group of international organisations for Native American and Indigenous research. Furthermore, the project group at Nord University consists of Associate Professor Astrid Marie Holand, who specialises in economic, political and welfare history as well as media history and journalism, and two doctoral research fellows on Greenlandic homemaking and Sámi historic housing policies and indirect assimilation. The project enlists several international partners. Senior Researcher Astrid Nonbo Andersen, at the Danish Institute for International Studies, is an expert on the History of Ideas and Memory Politics who specialises in past and present relations between Denmark and its former colonies, including Greenland, claims for reparations, apologies and Truth- and Reconciliation processes. She has an extensive network of scholars, activists and artists engaged in Greenlandic-Danish relations and is associated to the University of Greenland. Associate Professor Krister Stoor, Department of Language Studies, Director of Várdduo – Centre of Sámi Research at Umeå University, Sweden, specialises in Indigenous intellectual traditions, folklore, narratives and yoik, the Sámi way of singing. Dr. Stoor is Sámi and an active yoiker. Dr. Inge Høst Seiding, University of Greenland, historian and former archive leader at the National Museum, Archives in Greenland is an expert in Arctic social and cultural history, and Greenlandic colonial history, in particular marriages between European men and Greenlandic women between 1750-1850. Majken Paulsen, assistant professor, Nord University, who specializes in Sámi reindeer herding, climate change, colonization and human-animal interaction in the Arctic.

The expert group consists of researchers and Indigenous individuals with specific Indigenous competences and networks. Through seminars and dialogues with the project team, they will ensure that the project delivers high quality research with both theoretical, empirical and societal impact. They are listed as follows: Professor Britt Kramvig, at the Department for Tourism and Northern Studies, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, an expert on decolonisation and Indigenous/Sámi ways of knowing, locally embedded practice of reconciliation, memories and landscape. Professor in Nordic Studies Troy Storfjell, Pacific Lutheran University, a Sámi-American expert on Sámi and Indigenous studies, Indigenist criticism, decolonising methodologies and Indigenous intellectual and philosophical traditions. Associate Professor of Environmental History May-Britt Öhman, Center for Multidisciplinary Studies of Racism, Uppsala University, a Lule Sámi expert on gender, science and technology studies, resilience, decolonising and Indigenous theories and methodologies, racism and colonialism. Associate Professor Tone Huse, Department of Archaeology, History, Religious Studies and Theology, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, an expert on geographies and materialities of politics and leader of a project on climate change and the continuing effects of colonialism in Nuuk, Greenland. Dr. Anna Afanasyeva, PhD in Sámi history, an Russian Sámi expert in Russian Sámi history, assimilation, decolonisation and gender perspectives and also a lecturer at the Sámi University of Applied Sciences. PhD student Liisa-Ravna Finbog, Department of Cultural Studies and Oriental Languages, University of Oslo, an active duojár and Norwegian Sámi expert on Sámi archaeology and museology, and the relation between Sámi identities, Sámi handicraft (duodji) and Sámi museums. PhD student Áile Aikio, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Lapland, Finnish Sámi expert on indigenising and decolonising processes, especially how to indigenise cultural heritage research and management. Associate Professor Ebbe Volquardsen, Head of Department of Cultural and Social History, University of Greenland, expert on Danish-Greenlandic relations, collective memory, postcolonialism and decolonisation; Marianne Jensen, former Mayor of Ilulissat, former Minister, Government of Greenland. Maria Hernes, Stormen Sámi Center in Bodø, Norway; Stig Morten Kristensen, Duoddara Ráfe, Pite Sámi Center in Norway. Elen Ravna, Noereh, Norwegian Sámi youth organisation. We will also invite other Indigenous individuals and organizations to participate in our workshops during the project period.

The project has both a strong Indigenous and international profile, and will contribute to recruitment of future Indigenous scholars through its combination of PhD students, early scholars and more established scholars. It is interdisciplinary and brings together researchers from a range of fields such as sociology, social anthropology, history, journalism, history of technology, history of ideas, and literature. Finally, the project team has an even gender balance, with a female project leader.

3.2 Project organisation and management

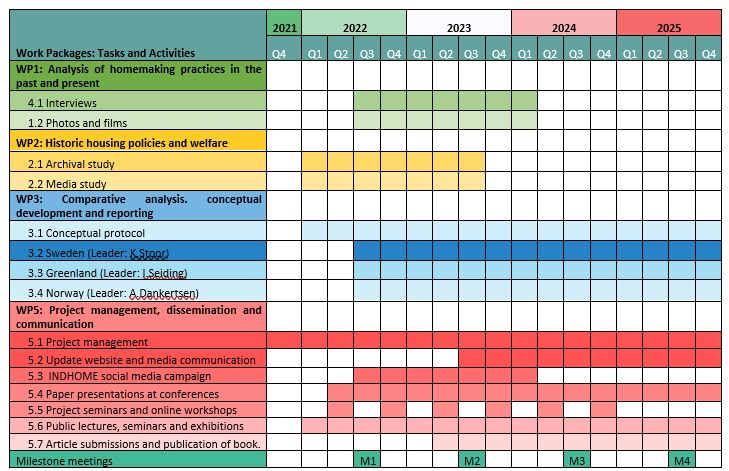

WP1: Analysis of homemaking practices in the past and present. WP-lead: A.Dankertsen Participants: A.Dankertsen, K.Stoor, M.Paulsen, PhD student 1.. Objectives: O4.1 Develop a theoretical framework for analysing homemaking practices. O4.2 Analyse homemaking practices as Indigenous cultural resilience and survivance in the past and present. O4.3 Analyse how homemaking practices are gendered practices. Methods: Qualitative interviews, observation, analysis of social media campaign. Task: T4.1 Give detailed descriptions of Indigenous homemaking practices in the past and present based on the data. Deliverables: D4.1 5 articles on Indigenous homemaking practices in the past and present in international peer-reviewed journals, such as NAIS: Journal of Native American and Indigenous Studies, Ethnicities, NORA – Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research, Acta Borealia, Home Cultures. D4.2 3 chapters in a book based on the project, published in an international high-ranked publisher such as Berghahn Books. D4.3 PhD thesis on Greenlandic homemaking.

WP2: Analysing housing and national policies. WP-lead: A.N.Andersen Participants: A.M.Holand, A.N.Andersen, K.Stoor, I. Seiding, PhD student 2. Objectives: O3.1 Develop a framework for analysing historic housing policies as indirect assimilation and colonisation. Methods: Historical document studies of housing policies and national policies. Tasks: T3.1 Study relevant historic archival materials in Norway, Sweden, Denmark and Greenland. T3.2 Analyse how historic housing policies can be seen as indirect assimilation and colonisation. Deliverables: D3.1 3 peer-reviewed articles in Scandinavica: International Journal of Scandinavian Studies, articles on historic Indigenous homemaking as resistance to assimilation in Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History and Contemporary European History.D3.3 2 chapters in a book based on the project, published in an international, high-ranked publisher such as Berghahn Books. D3.3 PhD thesis on historic welfare and housing policies and indirect assimilation of the Sámi.

WP3: Comparative analysis, conceptual development and reporting. WP-lead: A.M.Holand. + leaders in the 3 countries. Participants: All. Objective: Develop a protocol for major findings and a conceptual, comparative framework for analysis. Methods: Archive studies of housing policies and homemaking in the past, qualitative interviews, observations and photos of homemaking in the present, and social media campaign. Tasks: T2.1 Collect reports from country leaders. T2.2 Compare and contrast empirical findings and theoretical insights from WP3 and WP4. T2.3 Synthesise findings. T2.3 Develop comparative conceptual protocol for the project. Deliverables: D2.1 Protocol for major findings. D2.2 2 articles in peer-reviewed journals, such as Interventions: International Journal of Postcolonial Studies and AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples. D2.3 One chapter in a book based on the project, published in an international high-ranked publisher such as Berghahn Books.

WP4: Project management, dissemination and communication. WP-lead: A.Dankertsen Participants: All + expert group. Objectives: 5.1 Coordinate work packages and project progress. 5.3 Dissemination of results, reporting and communication. T5.1 Arrange project meetings, project seminars and workshops. T5.2 Report project to Norwegian Centre for Research Data. T5.3. Produce data management plan in accordance with GDPR. T5.4 Plan and coordinate project seminars, online webinars, paper sessions on conferences. T5.5 Coordinate dissemination activities. T5.6 Coordinate communication to media and social media campaign in cooperation with the Sámi youth organisation Noereh. Deliverables: D5.1 Report to NSD and maintain Data Management Plan. D5.2 Project seminars and workshops with project participants, the expert group and other invited participants on Indigenous homemaking. D5.3 Interviews and letters to editors in relevant media. D5.4 Social media campaign. D5.5 Exhibitions and seminars open to public at Indigenous centres.

Reference

- Mallet S. Understanding Home: A Critical Review of the Literature. . The Sociological Review. 2004;52(1):62–89.

- Vizenor G. Manifest Manners: Narratives on Postindian Survivance. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; 1999.

- Samanani F, Lenhard J. House and Home. In: Cambridge Encyclopedia of Anthropology. 2019.

- Walsh BJI. From housing to homemaking: Worldviews and the shaping of home. Christian scholar’s review. 2006;35(2):237–57.

- Mol A. Ontological Politics. A Word and Some Questions. . The Sociological Review (Keele). 2014;47(1 suppl.):74–89.

- Myrvoll M. «Bare gudsordet duger». Om kontinuitet og brudd i samisk virkelighetsforståelse. PhD thesis, University of Tromsø. 2010.

- Kramvig B. Landskap som hjem. Norsk antropologisk tidsskrift . 2020;1–2(31):88–102.

- Mulinari D, Keskinen S, Irni S, Tuori S. Introduction: Postcolonialism and the Nordic Models of Welfare and Gender. In: Complying with Colonialism Gender, Race and Ethnicity in the Nordic Region . Farnham: Ashgate; 2009. p. 1–16.

- Andersen AN. Ingen undskyldning : Erindringer om Dansk Vestindien og kravet om erstatninger for slaveriet. Copenhagen: Gyldendal; 2017.

- Dankertsen A. Samisk artikulasjon: Melankoli, tap og forsoning i en (nord)norsk hverdag. PhD thesis, University of Nordland. 2014.

- Wolfe P. Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native. Journal of Genocide Research. 2006;8(4):387–257.

- Minde H. Assimilation of the Sami – Implementation and Consequences. Acta Borealia . 2003;20(2):121–46.

- Hansen LI, Olsen B. Samenes historie fram til 1750. Oslo: Cappelen Akademisk Forlag. 2004.

- Lantto P. Lappväsendet. Tillämpningen av svensk samepolitik 1885-1971. . Växsjø: Davidssons Tryckeri; 2012.

- Homme L. Nordisk nykolonialisme. Samiske problem i dag. Oslo: Det norske samlaget. 1969.

- Eidheim H. Aspects of the Lappish Minority Situation. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. 1971.

- Stordahl V. Same i den moderne verden. Endring og kontinuitet i et samisk lokalsamfunn. PhD thesis, University of Tromsø. 1994.

- Olsen TP. I skyggen af kajakkerne – Grønlands politiske historie 1939-79. . Nuuk: Atuagkat; 2005.

- Janussen J. Fødestedskriteriet – Og Hjemmestyrets Ansættelsespolitik. Grønland. 1995;73.

- Nexø SA, Heinrich J, Nielsen L. Historisk udredning om retsstillingen for børn født uden for ægteskab i Grønland 1914-1974. Copenhagen: Statsministeriet; 2011.

- Thiesen H. For flid og god opførsel: Vidnesbyrd fra et eksperiment. Nuuk: Milik Publishing; 2011.

- Heinrich J. Rapport over projekt om Koncentrationspolitikken i Grønland 1940-2009’. Nuuk; 2016.

- Hansen UF. Tidligere og fremtidige problemstillinger i Grønlands boligpolitik. Grønlandsk kultur- og samfundsforskning. 2006;2004(5):53–66.

- Aman S, Desai C, Ritskes E. Towards the “tangible unknown”: Decolonization and the Indigenous future. Decolonization Indigeneity, Education & Society. 2012;1(1):1–13.

- Smith LT. Decolonizing Methodologies. Research and Indigenous Peoples. . Second edition. London and New York: Zed Books; 2012.

- Andresen A, Evjen B, Ryymin T. Kapittel 1. Introduksjon. In: Samenes historie fra 1751 til 2010. 2021.

- Olsen K. When Ethnic Identity is a Private Matter. . Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics. 2011;S1(1):75–99.

- Kirmayer LJ, Dandeneau S, Marshall E, Phillips MK, Williamson KJ. Rethinking resilience from indigenous perspectives. Canadian journal of psychiatry Revue canadienne de psychiatrie, . 2011;56(2):84–91.

- Tuck E. Suspending Damage: A Letter to Communities. Harvard Educational Review. 2009;79(3):409–28.

- Kuokkanen R. Towards an ‘Indigenous Paradigm’ from a Sami Perspective. The Canadian Journal of Native Studies . 2000;20(2):411–36.

- Bourdieu P. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1977.

- Kocka J. Comparison and Beyond. History and Theory. 2003;42(1):39–44.

- Werner M, Zimmermann B. Beyond Comparison: Histoire Croisée and the Challenge of Reflexivity. History & Theory. 2006;45(1):30–50.

- Kyllingstad JR. Norwegian Physical Anthropology and the Idea of a Nordic Master Race. Current Anthropology. 2012;53(S5).

- Bryld T. I den bedste mening. Copenhagen: Gyldendal. 1998.

- Drugge AL. Ethics in Indigenous Research: Past Experiences – Future Challenges. Umeå: : Vaartoe – Centre for Sami Research Publisher; 2016.

- Andersen AN. The Greenland Reconciliation Commission: Moving Away from a Legal Framework”. The Yearbook of Polar Law. 2020;11.