NAFO is about laughter, but you are not just a joke.

– Gabrielius Landsbergis, utenriksminister Litauen, 2023

NAFO is a living example of how to disarm Russian disinformation with humor, intelligence, and enthusiasm.

– Kaja Kallas, statsminister, Estland, 2023

med Shiba Inu som «hovedperson».

(Fotomontasje: Ukjent)

Hva er NAFO?

The North Atlantic Fellas Organization (NAFO) er en ideell grasrot bevegelse som så langt virker å spille en rolle i å motvirke russisk feilinformasjon rundt konflikten i Ukraina. NAFO er ikke en fasttømret organisasjon, men en gruppe frivillige fra hele den nordatlantiske regionen som er dedikert til å avsløre og motarbeide russisk propaganda og desinformasjonskampanjer.

Bakteppet for NAFO Fellas er det brutale russiske angrepet på Ukraina, og den uttalte hensikten er å motvirke den russiske propagandaen rettet mot et vestlig publikum, samt samle inn penger til Ukrainas forsvar.

NAFO er ikke et nytt fenomen, og kan vel sies å ha sitt utspring i de Litauiske alver.

Selv sluttet jeg meg til NAFO i juli 2023, dels for å gi et bidrag inn i kampen mot russisk desinformasjon og dels for å undersøke hvordan denne type grasrotbevegelse (såkalt «myk makt») kan fungere i kampen mot feilinformasjon i krig.

Den folkerettsstridige og ytterst brutale angrepskrigen Russland fører mot Ukraina, gjorde at jeg fant det vanskelig å holde på ideen om analytisk distanse. Når jeg deltok i, og utforsket, NAFO, så var det ut fra en klar stillingtaken mot Russland og for Ukraina.

Jeg var selvsagt innmeldt som privatperson (min Twitter-konto hadde ingen referanse til Nord universitet og ble heller ikke benyttet i min undervisning), men som de fleste akademikere er mitt primære fagfelt (Social Cybersecurity) ikke bare en jobb, men en «livsstil» og det jeg erfarer som privatperson vil selvsagt danne grunnlag for deler av min undervisning i informasjonssikkerhet.

NAFOs arbeid virker å ha vært spesielt effektivt innenfor sosiale medier. Gruppen har en stor tilhengerskare på Twitter, hvor de jevnlig legger ut faktasjekker og debunker av russisk desinformasjon. NAFOs tweets har blitt retweetet en rekke ganger, og de har bidratt til å øke bevisstheten om russisk propaganda blant deler av Twitters brukere, og via nyhetsmedia deler av offentligheten.

NAFO er også aktiv på TikTok og Facebook.

Den 13. juli 2023 ble NAFO Fellas tildelt the Star of Lithuanian Diplomacy, og blant andre Estlands statsminister Kaja Kallas er en stor tilhenger av NAFO.

I tillegg til arbeidet med sosiale medier, produserer NAFO også multimediejournalistikk. Gruppen har produsert en rekke videoer og artikler som avslører russisk desinformasjon og gir nøyaktig informasjon om konflikten i Ukraina. NAFOs arbeid har vært omtalt i flere medier, inkludert The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post og Sky News.

NAFOs arbeid er altså fokusert på kampen mot russisk desinformasjon, og gruppen har bidratt til å avsløre russisk propaganda og gi nøyaktig informasjon om konflikten i Ukraina. NAFOs arbeid har dermed bidratt til å informere offentligheten (i alle fall den delen som er på Twitter, TikTok og Facebook) om konfliktens sanne natur og motvirke russisk innsats for å så splid og forvirring.

Hvordan bli en NAFO Fella?

De som ønsker å hjelpe NAFO i deres kamp mot russisk desinformasjon, gjør gjerne følgende:

- Følger NAFO på sosiale medier og deler innholdet deres.

- Blir en NAFO Fella og bruker tiden sin frivillig til NAFO ved å besvare russisk desinformasjon. Medlemskap oppnås ved å vise til eksempel på egen donasjon til organisasjon/ forening som støtter Ukraina med penger og/eller utstyr. NAFO tar ikke selv i mot donasjoner, men viser til ulike hjelpeorganisasjoner/ foreninger. (Man trenger ikke å donere via NAFO (nettbutikk), eller til organisasjoner NAFO anbefaler, for å bli medlem. Selv ble jeg medlem via utstyrs- og pengedonasjon til Veteran Aid Ukraine.)

Selv små handlinger kan utgjøre en stor forskjell, så ved å følge og dele NAFO tvitring kan man bidra til å motvirke russisk desinformasjon.

Eller kan man det?

Tanken om å holde russiske propagandakontoer opptatt med «mot-trolling» minner om «Counter Scamming» (også kalt «Scam Baiting»), som var populært på begynnelsen av 2000-tallet og som også jeg tok del i. Da var motstanderne de såkalte «Nigeria-svindlerne». Hensikten med «mot-svindelen» var å latterliggjøre 419-svindlerne og få dem fra å forsøke igjen.

Akkurat som man kunne spørre seg hvor mye «mot-svindelen» mot Nigeria-svindlerne egentlig hjalp, må man også stille spørsmålet om NAFO Fellas egentlig oppnår noe vesentlig når det gjelder kampen mot russisk propaganda.

Noen spørsmål

Så langt har, som pekt på tidligere i dette innlegget, NAFO fått mye positiv omtale, men det er ikke gitt at en slik bevegelse er uproblematisk.

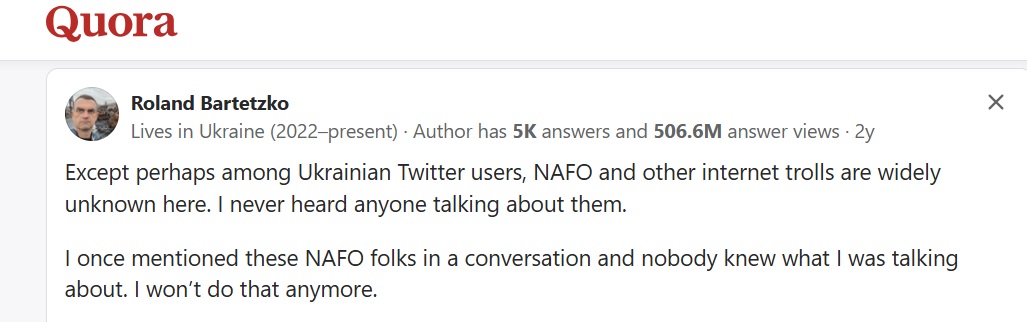

Oberstlt. Steve Speece ved the Modern War Institute, West Point, har påpekt at «Meme content shared in NAFO channels … is almost exclusively English language and presumably not intended for Russian audiences … These fora exist to generate content for the entertainment and status of their own members.»

Speece sin uttalelse setter fingeren på et viktig punkt med bruk av sosiale medier; når man virkelig ut til «alle» eller kun til egen menighet? Og blir denne type aktivisme først og fremst selvforherligelse av egen fortreffelighet, eller er det en effektiv form for informasjonskrigføring?

Devana, en Ukrainsk Twitter-bruker, har advart mot å angripe personer kun fordi de har et annet syn på krigen i Ukraina og påpeker at pro-russiske Twitter-brukere bør møtes med fakta da dette er en reaksjon som er mer «…effective to drive this person into a corner with facts, destroying all the fakes with which this person operates. This is a more intelligent attack by way of discussion.»

Dette er etter min mening et godt og viktig poeng. Desinformasjon bør møtes med saklige fakta. Men samtidig er et av de viktigste våpen i NAFOs kamp svart humor og latterliggjøring av russiske medier, politikere og nett-troll. Humor, selv den svarte varianten, kan være et både effektivt og legitimt våpen i kampen mot russisk desinformasjon. Men «mobbing» av personer som kun har et annet syn, er ikke bare forkastelig men kan også medvirke til å kvele reell demokratisk diskusjon.

Noen spørsmål jeg umiddelbart stiller meg etter å ha fulgt NAFO Fellas en stund, er:

- Hvor stor del av Internetts brukere blir egentlig nådd med denne type aksjoner, og hvor stor del av verden er nedslagsfeltet?

- Er NAFO-bevegelsen effektiv i kamp mot desinformasjon eller er det digitale slag i luften uten virkning?

- Kan NAFO utvikles til å bli en form for nett-vigilanter som ukritisk mobber og forfølger enhver som er uenig? Kan den utvikle seg fra å være en positiv motstand mot den russiske krigføringen i Ukraina, til å bli en «hatbevegelse»?

- Hvordan vil den stadige utviklingen av Internett (og derigjennom sosiale medier) påvirke denne form for «myk makt»? Vil f.eks. Elon Musk sine endringer av Twitter gjøre det vanskelig for NAFO både å «tvitre» og å få oppmerksomhet?

- Kan NAFO memes og hashtags, samt NAFO-svar til russiske nett-troll og offentlige instanser, utnyttes til å spre russisk desinformasjon?

Dette er bare noen av flere spørsmål som kan reises mot denne bevegelsen.

Oppsummert

NAFO virker å være en gruppe dedikerte og uorganiserte frivillige som muligens utgjør en viktig faktor i kampen mot russisk desinformasjon. Under denne «paraplyen» kan brukere av sosiale medier være med å bidra i kampen mot russisk desinformasjon på Internett. Men som alle typer sosiale media-bevegelser gir den grunnlag for flere kritiske spørsmål, og bør utforskes nøye av alle som har interesse for politisk bruk av sosiale medier.

Bruk av sosiale medier i krigstid – både som verktøy for desinformasjon og Fake News, og verktøy for bekjempelse av det samme – er interessant å ta inn i min undervisning i bruk av sosiale medier innen utdanningsfeltet (IKT og Læringsstudiene), og utforskning av NAFO Fellas vil kunne gi en praktisk bakgrunn for en slik undervisning.

Oppdatering

Den aktive deltakelsen via Twitter ble avsluttet i mai 2024, og resten av arbeidet vil foregå via gjennomgang av vitenskapelig og populærvitenskapelig litteratur som behandler NAFO.

De siste års endring av Twitter har gjort tjenesten til en plattform for mer aggressiv kommunikasjon, ikke minst i form av desinformasjon/ falske nyheter ol. Det ble rett og slett for slitsomt å opprettholde en tilstedeværelse der, og jeg ble også stadig mer i tvil om dette arbeidet rent faktisk hadde en virkning på Twitter. Jeg avsluttet derfor min Twitter-konto i mai 2024.

Jeg fortsetter imidlertid å studere, og ta del i, fenomenet som del av mitt arbeid innen digitale beredskap på Bluesky.

Leseliste

- Canonizing online activism: Memetic iconography in the North Atlantic Fella Organization

- The NAFO Fellas Are As Mighty As Ever, And They’re Ready to Fight Russian Propaganda

- Memes on the Battlements: A descriptive case study on the North Atlantic Fellas Organization

- Tastaturkrigerne

- Ukraine’s IT Army: Digital Resistance to Russian Propaganda

- Ukraine’s Information Front – Strategic Communication during Russia’s Full-Scale Invasion of Ukraine

- The Weaponisation of Memes

- ON TROLLS AND NUCLEAR SIGNALING: STRATEGIC STABILITY IN THE AGE OF MEMES

- Pro-Ukrainian Memes Against the 2022 Russian Invasion. A Cognitive Linguistics Perspective

- Memes, Language, and Identity During the Russo-Ukrainian War

- WeAreNAFO – Ukraines internationale Twitter-hær

- Social Media as a Recipient and Creator of Political Actions in the Context of the Security Crisis

- Fight Fire with Fire: Hacktivists’ Take on Social Media Misinformation

- Shielding Democracy: Civil Society Adaptations to Kremlin Disinformation about Ukraine

- Who are the NAFO ‘fellas’ fighting misinformation online?

- Elf-Determination: grassroots movements spreading positive narratives on social media

- Digital Warfare and Peace: Learning from Ukraine’s Response to the Russian Invasion

- #NAFO and Winning the Information War: Lessons Learned from Ukraine

- Lithuania Reacts: Confronting Russian Manipulation Techniques

- REGULATING A ‘CYBER MILITIA’ – LESSONS FROM UKRAINE, AND THOUGHTS ABOUT THE FUTURE

- My war: participation in warfare