…not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted.

William Bruce Cameron, 1963

Academic social media: game-changer or smoke and mirrors?

We’re told to tweet, post, and share to boost impact—but does it really work? Behind the glossy badges and inflated scores lies a harsh truth: most “engagement” is just academics talking to academics. Add copyright risks, endless profile updates, and metrics you can hack in minutes, and the promise of outreach starts to look like a digital masquerade. Real influence? It still comes from solid research, trusted networks, and meaningful teaching—not chasing likes.

Climbing the Social Media Pole

I’ve been fooling around on Internet since 1994 and most of the time in a professional capacity. Seriously influenced by people like Howard Rheingold, and curiously exploring the various possibilities for academic use of WWW, I’ve built quite a presence online over the years using every Social Media (or Web 2.0 as it was once called) tool as soon as it appeared. But as everyone that have been active users of Internet know, keeping track of multiple profiles, and keeping them alive and updated, is exhaustingly time consuming. At a certain moment, I reached a point where I felt nauseated and tired of everything connected with the Net and withdrew from almost all online tools.

But it is not easy to keep completely away from social media. As a conscripted officer in the Norwegian Civil Defence with staff duties (2013 – 2021) Facebook was the main source of information on what went on within my Civil Defence district. And truth be told; I also missed the online contact with my old team mates from the Home Guard School and Training Centre (2012). So back I went, creating a new profile. As a dean, I had some lecturing so Twitter became, again, a useful tool. But that was it, I thought. No more profiles on the Net.

And then, in 2014, I went back to full time lecturing and everything changed. Because now, having papers publicised in international peer reviewed journals is no longer enough. Our university managers, as well as our lords and masters from the Ministry of Education, speaks of reaching out to a broader audience and that as much as possible of our work are to be open access. And suddenly one is urged to go back on the Net and immerse one selves in various online services.

The tools and all the work that follows

There are infinite possibilities of reaching far and wide using various social media services, and let’s face it; it is difficult to reach out to a large audience from a scientific journal. Not only are these journals mostly read only by our colleagues, but the possibility of having our journal entries cited by fellow researchers are slim. Not because we necessarily write badly or that our work is uninteresting, but because so many of us works within small niches. I have my selves spent most of my academic career pondering how to get computer science students enthusiastic about Social Informatics, or how to motivate students of asynchronously online courses to carry on. While this is important enough for me, and hopefully also for my students, it is neither rocket science nor is it the most popular scientific field in the world. But will enrolling in various Social Media services help you to reach out to a larger audience? Not necessarily.

Let’s have a look at some of the things you might do to be visible as an academic online. Many university managers will point you in the direction of ResearchGate.net and Google Scholar. The last one in order to create an overview of where and how often your papers are cited by others, and the first one because… well, I guess because “everyone else” is there and this is the only academic profiling tool they know of (a part from Google Scholar). So, by creating profiles on these two services, all your troubles are over right? Wrong! To utilise both Google Scholar and ResearchGate demands quite an effort. Like most social media profiles, they need constant updating to stay interesting and/or correct as for your list of publications, and preferably they should be paired with other tools like Twitter, ORCID, Impactstory, Mendeley and Quora. This will increase your online presence and could work favourably as for your so called “impact score”.

ResearchGate have developed into a well-known social networking site for researchers, where they may share papers, ask and answer questions, and find collaborators. In order to use the site, you need to have an email address at a recognized institution or to be manually confirmed as a published researcher in order to get an account. After signing up you create your user profile and might start uploading research papers, data, chapters, presentations, etc. You may also follow the activities of other users and engage in discussions with them, and this way start building a network and perhaps even enter into research cooperation with one or more of your contacts.

Impactstory is an open source, non-profit and web-based tool that provides altmetrics to help researchers measure the impacts of all their research outputs—from traditional ones such as journal articles, to alternative research outputs such as blog posts, datasets, and software. You may use your Twitter account to sign up, but how much this site uses your Twitter activity to measure your impact score is unclear to me. Signing up to Impactstory quicly pushes you to ORCID, as this is the key tool Impactstory uses to gain an overview of your publications. According to ORCID its aim is to aid «the transition from science to e-Science, wherein scholarly publications can be mined to spot links and ideas hidden in the ever-growing volume of scholarly literature». They also give the researcher a possibility to have «a constantly updated ‘digital curriculum vitae’ providing a picture of his or her contributions to science going far beyond the simple publication list».

Mendeley is a desktop and web program produced by Elsevier for managing and sharing research papers, discovering research data and collaborating online, and Twitter I guess does not need much of an introduction. To use Twitter as a dissemination tool you must have followers, preferably many. Your follower count is considered a measure of your influence. The more followers you have, the more you’ll attract, and – in theory – the more you can use your influence to reach your peers, students and other interested parties. But to get followers you have to put in a lot of time of strategic actions, and at the end of the day you might not really know if any of this had any effect or mattered at all. There are no free lunches in the world of Social Media, and just creating some profiles and then sit back and relax is not really an option.

Since all this is mainly about creating and measuring “impact”, utilising digital tools, the more activity you have online, the better. But most of these tools give poor results if you do not already have international papers. So, if you are an academic who so far have been content with focusing on excellent lecturing and close contacts with students, you will have to make quite an effort in order to have any significant use of these tools. And as soon as you have created all these profiles you are trapped in a never ending story of continuously updating them.

The not so open access, legal problems and some unsettling thoughts

ResearchGate strongly encourages its members to upload scientific papers, and many do so. This creates the impression that the platform is an open-access provider. However, there are two major issues with this. First, uploading journal articles usually breaches copyright law. Second, others must sign in to ResearchGate to read these papers. In reality, this makes it a closed-access service, potentially hosting a large number of copyright violations. Academia.edu, a similar social media site, faces the same problems.

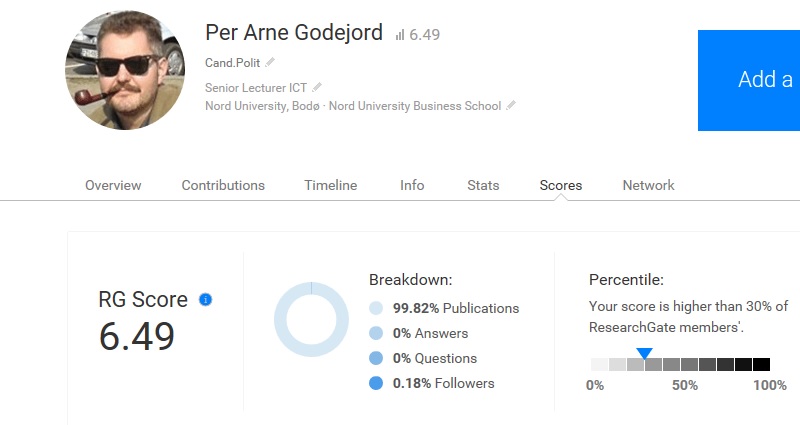

A third issue with ResearchGate, when I first wrote about this, was its use of scores. These scores were meant to reflect your “impact”, but the calculation was not transparent, making it hard to understand what data they were based on. Statements like “Your score is higher than 30% of ResearchGate members” encouraged, in my view, an unhealthy focus on questionable metrics and even the possibility of “gaming” the system.

But what does “impact” really mean? Traditionally, we look at journal rankings or how often our work is cited. Sites like ResearchGate and Impactstory aim to create a broader measure of impact, but without clearly defining the term. Would your score rise if you follow researchers with large networks and high RG scores? What if someone visits your profile using a proxy that randomly changes their IP address? Does a mention in a Wikipedia article, written and edited anonymously, truly reflect impact? Would adding a link to your RG profile on Twitter increase visits—and if so, would that affect your RG score? Twitter might drive curious visitors to your profile, but does that mean your work is reaching a wider audience? I don’t think so. A click on a profile link doesn’t necessarily show genuine interest. And who are your Twitter followers—members of the public, or fellow academics and your own students? If it’s the latter, we’re back to the old problem: journal papers being read only by a small circle of peers.

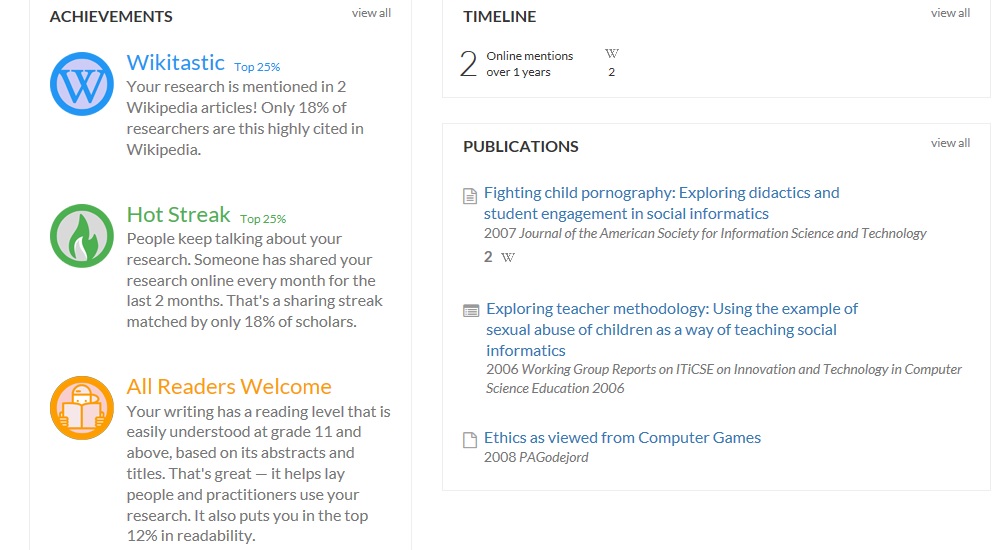

In 2017 some of my metrics looked like this:

2. Impactstory:

3. ResearchGate

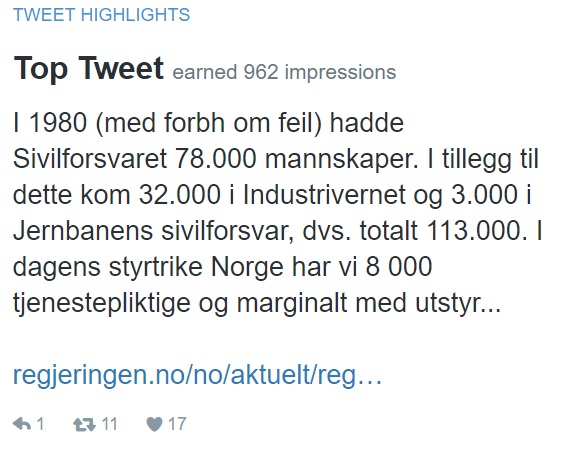

The statistics for my tweet are rather straight forward, at least to a certain extent. It seems that 180 persons interacted with it in various ways. But of course, on the Net the systems can only count IP-addresses, and therefore what may seem like individual interactions might not necessarily be so. How the number of 9, 357 is figured out is not clear, neither what «impressions» really entail or why it should matter in the «real world». Impactstory uses the gamification element of badges. Since this tool also focuses on open access, you might get an Open Access badge. I did not get it as I have my papers in ordinary journals, but by uploading a large number of drafts, or even just resumes of papers in for instance ORCID I would not be surprised if Impactstory considers this an adherence to the principles of open access, and award you a badge. And in ReserachGate I achieved the score of 6.49, but have absolutely no clue as to how RG calculated this.

Wanting to understand how ResearchGate counted its impact points in 2017, I repeated the experiment done by professor Kjetil Haugen in 2015. Cloaking my identity using various proxies I viewed my own profile, read and downloaded selected works, and additional shared selected works using one of the Social Media tools RG have made available for this purpose. This was made easy since my selected tool let me share links by simply creating an account with no checking for authenticity. When I started the experiment 1th of March 2017 my RG score was 4, but by the end of the experiment on 10th of March the same year it had increased to 6.49. My conclusion therefore is that nothing has changed since Haugen did his experiment in 2015. In my opinion this renders RG useless as a valid system for measuring individual researchers academic impact. The same goes for Impactstory, and I suspect it will also be true for most of the sites that claims to measure your impact.

My main problem with these Academic Social Media tools is why should these scores matter? They are easy to manipulate, and does not give any real evidence of scientific impact or the individual researchers willingness to be part of the open access movement. Neither do they necessarily give a clear picture of a researcher’s true network. Twitter, who as such is not an Academic Social Media, but might be used as a tool for dissemination, is a great tool to use with students in specific settings, but so far I have found little to prove that my use of it had any impact outside my lectures. But this might be my fault entirely.

Unclimbing and reclimbing the Social Media Pole

Despite (or perhaps because of) having participated in various Social Media for years I again deleted most of my social media profiles in 2017 and 2021. The amount of work you must put into these tools far outweigh any gains they might have and only provides an unnecessary distraction. So far, my most successful international contacts and cooperation’s have been the result of personal acquaintance, not any presence on Academic Social Media.

I re-entered Twitter in 2020 and this time I decided to focus on Preparedness and Cyber Security. My motivation for getting back to Twitter was primarily to keep me informed on various Cyber Security and Preparedness matters. Most of my tweets are done automatically via my Paper.li newspaper.

Looking at my Twitter Analytics two years later, in 2022, I was left with the same question as before; Of what use is this? Twitter has its merits as a tool for discussing topics of interests with other professionals , but not as a tool for dissemination to a broader general public.

Nice that my tweet above got 11 retweets and 17 likes and earned "impressions" but I doubt that it had any impact on parliamentary politicians will to invest in Civil Defence.

Another example of how a Twitter account tries to create attention to an article is this from Alltinget.no:

In May 2024 I again deleted my account on Twitter (now rebranded as X), on the grounds that it had become a «dark» area for constant disinformation and fake news. I had enrolled myself in the work of NAFO, but in the end the whole platform seemed irrelevant as a serious arena for communication and with few or little possibilities for actual combating Russian propaganda.

What remains of my social media presence outside blogging is a private account on Instagram, an account on Pinterest (none of them in use, but not deleted), and a Flickr account linked to the Getting Involved project. And I have kept my main YouTube account, but only as documentation of my use of trigger videos in teaching.

In June 2025 I decided to explore Bluesky and in December 2025 I again created a profile on Linkedin, albeit without much enthusiasm (which is reflected in my activity there).

And why this return to two social media platforms, despite my distaste for these services? The answer is twofold: partly because I teach about the professional use of social media – including their role as tools for spreading fake news – and partly because it might seem odd that an Senior Lecturer in Computer Science, who has been an active user of the Internet/Web for dissemination since 1995, is not visibly present on any social media in 2025.

Some last ponderings

It all comes down to trust, but even so if we absolutely must be counted and measured, I think the most sensible is to forget about metrics offered by so called Academic Social Media tools and rather focus on papers in scientific journals (though, we have to deal with dubious impact factors also here), newspaper articles (that might reach the general public), and student assessments (that will tell us if we reached our students or not).

Also, I think it would be worthwhile to establish a system for peer reviewing of online lecture resources, like the former Intute project. This might encourage researchers to utilise blogs, wikis, etc. as parts of their lecturing, as well as potentially reaching a larger audience than just via journals. Though, again, we do not really know if the public actually search for such blogs, or that our particular field will generate any public interest. In fact, a small study done in 2013 concludes that most academic blogs are made for our professional peers, rather than for the general public. So perhaps we should be more than happy if we just manage to reach our students hearts and minds through our blogs and other social media tools?

While I am confident that most academics use social media tools appropriately, platforms such as ResearchGate and Impactstory may encourage what could be called “Facebook behaviour”: presenting an idealised image of thriving research activity and professional happiness. These tools can serve as mechanisms for maintaining visibility and securing one’s academic profile—a complex set of measures that might mislead management about the true presence and impact of one’s work. In short: Maskirovka, the academic way.

Addendum: What’s Changed as of December 2025

Since this post was first written, the academic communication landscape has evolved significantly:

- ResearchGate Metrics & Copyright

- The RG Score was retired in 2022; current indicators (e.g., “Research Interest Score”) remain opaque and should be interpreted cautiously.

- A 2023 settlement with major publishers introduced upload‑time rights checks and private sharing options, reducing—but not eliminating—copyright risk.

- ORCID and Persistent Identifiers

- ORCID adoption is now near‑universal in many regions and required by funders and journals. Maintaining an up‑to‑date ORCID record is essential for compliance and interoperability.

- ORCID adoption is now near‑universal in many regions and required by funders and journals. Maintaining an up‑to‑date ORCID record is essential for compliance and interoperability.

- Open Access Mandates

- Plan S continues to shape European OA policy, and the U.S. OSTP memo requires immediate public access to federally funded research by Dec 31, 2025. Repository‑based OA is now the default route; social networks should serve as signposts, not primary access points.

- Plan S continues to shape European OA policy, and the U.S. OSTP memo requires immediate public access to federally funded research by Dec 31, 2025. Repository‑based OA is now the default route; social networks should serve as signposts, not primary access points.

- Social Media Shifts

- X/Twitter’s role in scholarly communication has diminished due to API restrictions and rising misinformation. Many academics have migrated to Bluesky or other platforms, though network effects remain a challenge.

- X/Twitter’s role in scholarly communication has diminished due to API restrictions and rising misinformation. Many academics have migrated to Bluesky or other platforms, though network effects remain a challenge.

- Altmetrics and Impact Evidence

- Altmetrics are best treated as early attention signals, not definitive measures of impact. Combine them with citations, policy uptake, and qualitative evidence for a robust narrative.

- Altmetrics are best treated as early attention signals, not definitive measures of impact. Combine them with citations, policy uptake, and qualitative evidence for a robust narrative.

- Metric Manipulation Risks

- Citation gaming and AI‑generated content have increased, especially on Google Scholar.

I feel my core message is still relevant: Likes and follower counts are not proxies for societal impact. We should prioritise quality research, compliant open dissemination, and meaningful teaching evidence over vanity metrics.

Some interesting links for further reading

- How to promote your research on social media

- Scholarly use of social media and altmetrics: A review of the literature

- What Is the Predictive Ability and Academic Impact of the Altmetrics Score and Social Media Attention?

- Grand challenges in altmetrics: heterogeneity, data quality and dependencies

- Scholarly Tweets: Measuring Research Impact via Altmetrics

- How to Track the Impact of Research Data with Metrics

- The ResearchGate Score: a good example of a bad metric

- Measuring impact in the age of altmetrics

- Ein Vergleich für Forscher unter sich: Der Researchgate Score

- Gaming the Metrics: Misconduct and Manipulation in Academic Research

- Manipulating Google Scholar Citations and Google Scholar Metrics: simple, easy and tempting

- How can academia kick its addiction to the impact factor?

- Reading List: Using Social Media for Research Collaboration and Public Engagement

- Are websites and blogs an effective outreach tool for academics?

- Digital Presence of Norwegian Scholars on Academic Network Sites—Where and Who Are They?

First published on LiveJournal.com: 03/10/2017. Edited and updated: 23/06/2021, 02/11/2022, 08/05/2024, 28/06/2025 and re-published 08/12/2025.